This post is from the LSAT Free Help Area on our website. Want to get even more free LSAT help? Check it out!

While preparing for the LSAT, students will undoubtedly encounter a wide variety of suggested test taking strategies. Unfortunately, one of the more commonly advocated approaches, particularly with regards to the Logical Reasoning sections, is the use of Venn diagrams1. Despite their popularity with certain test-preparation programs, Venn diagrams are inappropriate for the Logical Reasoning problems test takers encounter on the LSAT because they force the test taker to make certain dangerous assumptions while diagramming.

Some Background

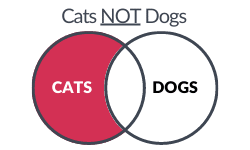

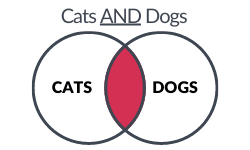

Venn diagrams are useful for their simplicity in illustrating linked logical terms (and, or, not) in situations where the variables are clearly distinct from one another but potentially share similar characteristics. For instance, below are Venn diagrams applied as they were originally intended:

Variables: Cats, Dogs

The red areas represent the areas selected by the operator phrases “and,” “or,” and “not.” The red “and” area would represent a common characteristic shared by the two groups, such as four legs. The “or” diagram shows that this scenario would include all cats or all dogs or both. The final operator, “not,” shows a complete exclusion of one of the groups (and, hence, the commonly shared area as well). In this case, the dogs are excluded.

Not-So-Simple Scenarios

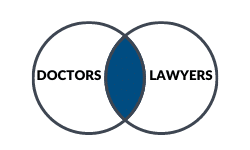

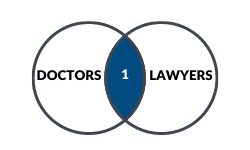

However, the Logical Reasoning problems of the LSAT are based on a number of logical statements that do not always possess the same implied limitations. Consider the following example: Some doctors are Lawyers. According to this simple statement, at least one doctor is also a lawyer. Thus, most students would create the following Venn diagram:

The blue, overlapping area represents the doctors who are also lawyers. However, because of the vagueness of “some,” the diagram above only represents one of a number of different possible interpretations of the sentence. For example, the sentence as used above can also be correctly interpreted in each of the following ways:

- One doctor is a lawyer.

- Most doctors are lawyers.

- All doctors are lawyers.

- Most lawyers are doctors.

- All lawyers are doctors.

- Doctors and lawyers represent the exact same group.

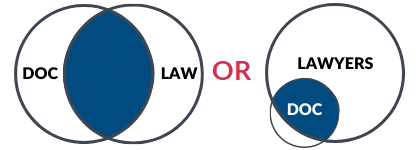

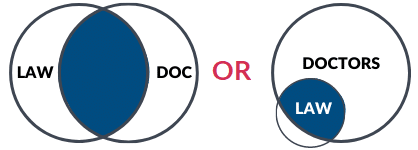

It becomes quickly apparent that the preceding Venn diagram, though valid in one sense, assumes entirely too much from such a general statement. In fact, to adequately represent “some doctors are lawyers” with Venn diagrams, countless possibilities exist. Consider just the six possibilities previously mentioned with representative Venn diagrams:

One doctor is a lawyer.

Most doctors are lawyers.

All doctors are lawyers

Most lawyers are doctors

All lawyers are doctors

Doctors and lawyers represent the same exact group

Therefore, by choosing a single initial Venn representation of the statement “some doctors are lawyers,” the unwitting test taker ignores numerous other possible interpretations of the sentence.

Logical Reasoning Terminology

This surprising problem arises solely from the test makers’ use of the word “some.” Although real-world speakers typically understand “some” to mean “a portion of, but not all,” the logical terminology of the LSAT allows for a much broader definition, represented most accurately as “at least one (and possibly all).” One of the most crippling limitations of Venn diagrams is that there is no quick and accurate way to effectively diagram commonly used LSAT phrases such as “some” or “most” or “not all,” to name a few. Test takers are then left with the challenge of either diagramming all of the necessary representations (much too time consuming), or with attempting to negotiate the pitfalls of a difficult problem with an inadequate diagram (inaccurate and therefore dangerous). Unfortunately, an unaware student almost always chooses the latter and is now in a weak position to attack answer choices.

Further consideration is required when attempting more complex problems. Consider the following example:

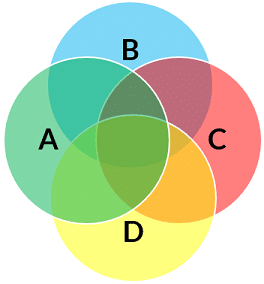

- The Island of Utopia is composed of four tribes—A, B, C, and D—who coexist under the following conditions.

- Some A’s are B’s.

- Some B’s are C’s

- and Some C’s are D’s.

Even with only four variables represented in the most basic way, a possible Venn diagram encompassing only one scope of the problem’s possibilities looks like this.

Each colored area represents a different grouping scenario. Again, this does not even begin to cover all of the possible interactions allowed by the game’s premises. For instance, all of A could be B, or A and B could be the same group, etc. A scenario with five variables becomes even more complex, and so on.

Encountering These on the LSAT

The odds of the average test taker correctly diagramming the above scenario are clearly quite small. Moreover, with a timed test like the LSAT, there simply is not time to consider each possible representation. The incorrect inferences that follow from a typical Venn diagram are, in fact, often the basis of the test’s wrong answer choices, as the test makers attempt to exploit the student’s dangerous assumptions.

Clearly, Venn diagrams are quite useful for visually explaining certain simple and specific relationships. However, the implied assumptions necessary for these “real-world” interactions do not often apply to similar scenarios on the LSAT, and approaching Logical Reasoning questions with Venn methodology inevitably creates unsubstantiated inferences and, ultimately, wrong answer choices.

Thankfully, there are alternative diagramming tools designed specifically with Logical Reasoning and the LSAT in mind. The diagramming methodology taught in the PowerScore full-length LSAT course and the PowerScore LSAT Logical Reasoning Bible is a simple but comprehensive system allowing for an effective, accurate representation of such phrases as, “some,” “most,” and “not all,” without the inherent, misleading assumptions associated with Venn diagrams.

Leave a Reply